PTIM 2020 Guest Blog - Geneva

This guest blog, from the University of Maryland, talks about the evolution of Geneva, and how it can play a part in learning how to evade censorship.

Geneva: The Algorithm Spotting Censorship Evasion

Kevin Bock and Dave Levin, University of Maryland

For decades, network censors have played a cat-and-mouse game against the activists and researchers that seek to evade them. Unfortunately, this game has historically favored the censor: the traditional approach to creating a new evasion strategy is to first measure and understand censors’ secretive infrastructure, and apply human intuition and ingenuity to (hopefully) arrive at a clever insight into how to circumvent it. Manual discovery processes can take months or years, and when a censor changes its infrastructure, it can force researchers back to square one, ultimately leading to long lulls in evasion success.

We have been working to give evaders the advantage in the censorship arms race.

We have developed Geneva (Genetic Evasion), a genetic algorithm that automatically discovers and implements censorship evasion strategies. Geneva inverts the traditional process for discovering evasion strategies. With Geneva, the first step is discovery (which is automated); understanding why it works (which requires human insight) comes afterwards.

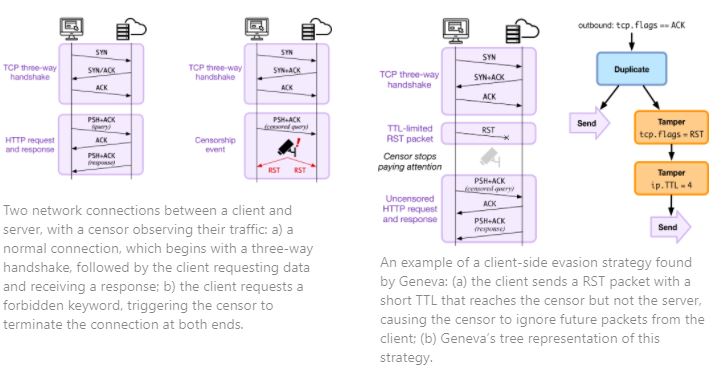

Geneva discovers a particular kind of censorship evasion strategies: those that modify network traffic at one end of the connection, confusing the censor, without confusing the host at the other end of the connection. A canonical example of this would have the client inject a TCP RST packet with a TTL large enough to reach the censor but not large enough to reach the destination—as a result, the censor would believe the connection is torn down and stop paying attention, while the server is none the wiser. Geneva is not the first to implement packet-manipulation strategies, but it is the first to automate their discovery and the most complete: in initial testing, Geneva re-created almost all previously published packet-manipulation strategies in an afternoon. A canonical example of this would have the client inject a TCP RST packet with a TTL large enough to reach the censor but not large enough to reach the destination—as a result, the censor would believe the connection is torn down and stop paying attention, while the server is none the wiser.

We trained Geneva client-side inside China, India, Iran, and Kazakhstan, for each of the protocols they censor (combinations of HTTP, HTTPS, DNS, FTP, and SMTP). To date, Geneva has successfully found dozens of novel censorship evasion strategies across the four countries. These can enable activists, users, and researchers to communicate without interference from censors. These can enable activists, users, and researchers to communicate without interference from censors.

Geneva is fast—typically taking only 1-2 hours to discover new evasion strategies, even against new forms of censorship it has never seen before. Perhaps most importantly, Geneva is free from the biases of human researchers; it has discovered circumvention strategies that prior work (and even we!) thought simply “should not” work.

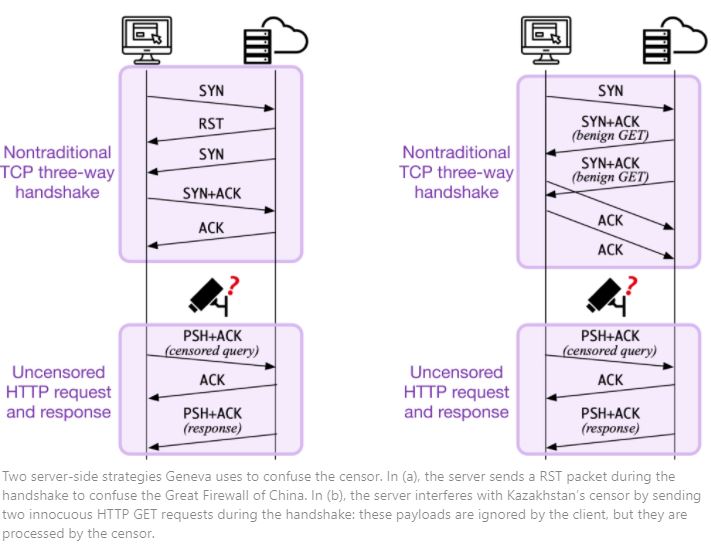

One of Geneva’s most surprising findings is that censorship can be evaded without requiring clients to install any evasion software whatsoever (not even Geneva). Instead, the server evades censorship on the clients’ behalf by manipulating its own traffic to the client. These so-called “server-side” evasion strategies allow content to be reachable by all users within a censoring regime, including users who lack the technical knowledge to use evasion tools, or users who did not realize they were being censored in the first place.

In a sense, server-side evasion “shouldn’t” work: before censorship takes place, a server typically sends very few packets (as little as just a single SYN/ACK packet while establishing a new connection) before the client’s forbidden request triggers censorship. Because of the server’s limited involvement, it has long been thought that purely server-side censorship evasion was not possible.

Fortunately, Geneva did not know that it “shouldn’t” work. We altered Geneva to be able to run from the server-side, and trained it against four countries (China, India, Iran, and Kazakhstan) across five protocols (DNS-over-TCP, FTP, HTTP, HTTPS, and SMTP). To date, it has found 16 server-side strategies, all of which work with completely unmodified clients.

Two server-side strategies Geneva uses to confuse the censor. In (a), the server sends a RST packet during the handshake to confuse the Great Firewall of China. In (b), the server interferes with Kazakhstan’s censor by sending two innocuous HTTP GET requests during the handshake: these payloads are ignored by the client, but they are processed by the censor.

Because Geneva operates by manipulating packets, it composes well with a wide range applications. We are continually extending Geneva’s capabilities and training it against new protocols and censorship infrastructure. For more information, articles, and source code, or if you are interested in incorporating Geneva into your censorship evasion tool, please visit https://censorship.ai.